Losing weight: Science and tourism in the City of Light

After staying in Paris for several months, I found myself doing what I normally do in Champaign-Urbana: riding a bike and working on a science documentary. The two activities are related, but not in a way I'd imagined.

•

Weights and measures are revised like other infrastructure. Public bikes are much more common today.

Note: This piece appeared in the Champaign-Urbana News Gazette, May 28, 2013. An online version is available.

After staying in Paris for several months, I found myself doing what I normally do in Champaign-Urbana: riding a bike and working on a science documentary. The two activities are related, but not in a way I'd imagined.

I traveled to Paris to visit the kilogram, the subject of my film. A "kilogram" is more than an idea; there are kilogram standards in government labs and commercial plants around the world. But the French created the original kilogram and meter in response to the Revolutionaries' insistence on equality in all things.

In France of the 1780s, units varied from town to town. Country merchants faced different measures when selling such necessities as wheat, wine, and fabric in Paris. Trade within France was broken, and King Louis XVI formed a commission of his nation's premier scientists to standardize their measures.

Weathering the political instability of the following years, the commission (which included scientists Pierre-Simon Laplace, Joseph Louis Lagrange and Antoine Lavoisier) performed its job admirably and in 1795 proposed a new system of units "for all time, for all people."

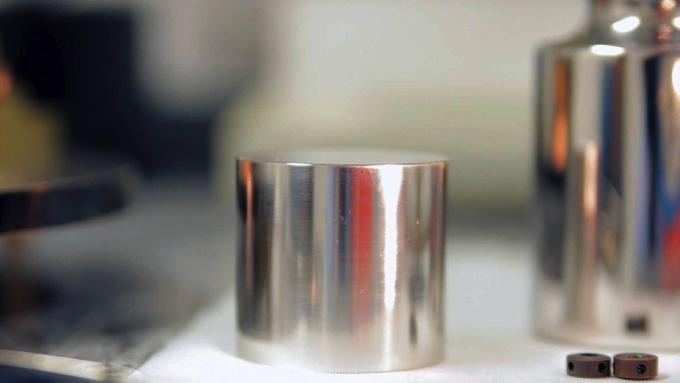

Two units, the meter and the kilogram, were ultimately defined by platinum-iridium artifacts of special shape and size. During 1796-97, official copies of the meter were installed throughout Paris so that anyone could verify their own measuring sticks, anytime.

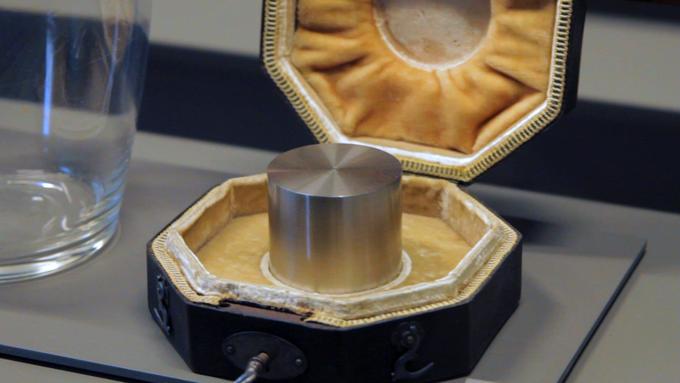

In 1875, an international consortium adopted the new measures and forged a platinum-iridium cylinder, called the International Kilogram Prototype, whose mass was defined to be exactly 1 kilogram. (You may have heard how the kilogram is "losing weight." What that means is other kilograms appear to be heavier than the IPK after 120 years of comparisons.)

As more countries accepted the metric system, a long chain of mass standards reached through space and time, radiating from the IPK.

Eventually standardized measures became a government-managed infrastructure, like public phones or the 18,000 public Velib' bicycles, now available throughout Paris.

Like the kilogram and meter, these public bikes solved a practical problem. To ease auto congestion, the mayor of Paris, Betrand Belano, launched the Velib' system in 2007. (Velib' is a hybrid of the words velo and liberte.)

And similar to a new measurement system, Velib' disrupted the status quo: parking spaces were replaced with docking stations and bikes lanes were squeezed next to cars. But after a few years of resistance, vandalism, and logistics issues, the Velib' bikes became part of daily life. They're easy to use and quite fun. The docking stations are placed near Metro stops, and so close that you can often stand at one and see another in the distance.

Here's how Velib' works: You buy a pass for 1, 7, or 365 days, and within that duration, you can check out a bike for up to 30 minutes. If you return the bike to any station within 30 minutes, there's no late fee. Five minutes after returning a bike, you can check out another. And if you return a bike at the top of Montmartre or another high-elevation station, you're rewarded with a 15-minute bonus on your next trip. Their relatively short rental time — and stocky build — reflect their intended purpose: quick trips around town.

The bicycles have three gears, shopping baskets, chubby tires to handle cobblestone and electronics to talk to docking stations. Despite their weight (22.5 kg) and rental tracking via credit card checkout, you will likely spot an abandoned Velib' at the bottom of the Seine. And Velib'ers communicate in code: a seat turned backward indicates that bike needs maintenance.

So how was it commuting by bike, in one of the world's most densely-populated cities? Very scary at first. Sharing one lane are the largest, wildest and slowest vehicles: buses, motorbikes and bicycles.

To go left in the Place de la Bastille, I would make three right turns. My first trip home from Montmartre took more than an hour. In a few weeks, I could do it in 29 minutes.

Gyms are expensive in Paris, so I used Velib' for exercise as well as commuting. The rental history became my exercise log. I signed up for the one-year "Passion" plan, which allows 45 minutes before trading in, instead of the usual 30. Americans would name the plan "ultra" or "discount" or "cardio-fit," but the French infuse passion whenever possible.

And Goethe accurately observed that "he who would be beautiful must suffer" — many Parisian women cycle in short skirts and high heels.

To my happy surprise, after weeks of strawberry croissants from Le Grenier pain, I still lost 2.7 kg by cycling and walking so much. I never heard of anyone who lost weight in Paris. Except the kilogram.